The Power of Moses, Memory & Immigrant Communities in The Lonely Londoners

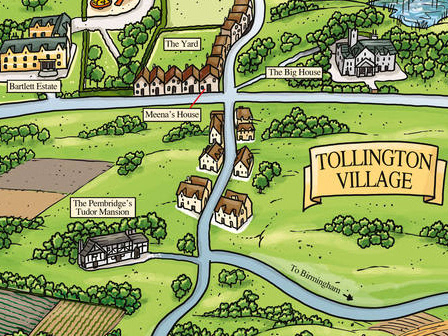

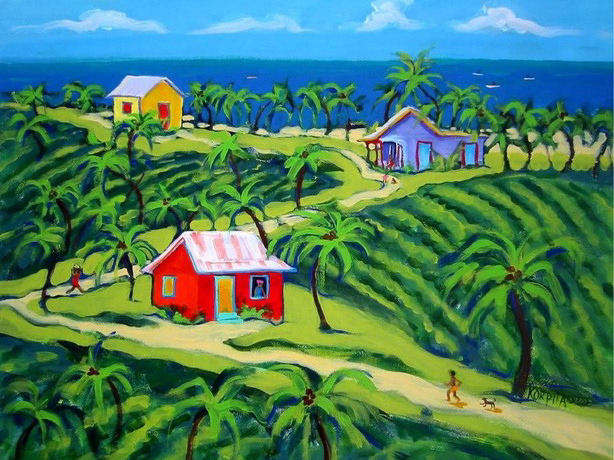

Imagine this: it’s the 1950s, and you have just arrived in London on the first day of your brand-new life. You bravely stride into the bustling streets, where the air is heavy with the scent of opportunity, distinguishable by the potent, bitter taste of prejudice. This was the reality for Moses Aloetta in Sam Selvon’s The Lonely Londoners. Set against the backdrop of post-war Britain, The Lonely Londoners reflects the arrival of West Indian immigrants seeking a better economic environment. The Windrush generation, a period in history named after the ship that brought the first major wave of Caribbean immigrants to Britain in 1948, faced severe systemic racism and social marginalization.

Selvon uses the character Moses to demonstrate how his relationships with memory and nostalgia contribute to the close-knit community he and his fellow Caribbean immigrants create to cultivate a sense of belonging and solidarity within the ignorant, racist English society of London. Through Moses’ experiences, Selvon illustrates how the longing for a distant homeland and the recollection of shared memories serve as powerful mechanisms for overcoming the alienation and discrimination faced by the novel’s immigrant characters. In this essay, I will argue that Moses emerges as a striking embodiment of this resilience and solidarity, fostered by a shared remembrance of the past he shares with his fellow immigrants. His character vividly proves how nostalgia and memory ultimately become essential in forging bonds and navigating the adversities of life.

Moses emerges onto the pages of The Lonely Londoners as a multifaceted character who wrestles with the dual desire to assimilate into English society and to preserve his Trinidadian heritage. He is wise, cautious, soft-hearted, empathetic, and the true antithesis of the innocence of arrival. Moses becomes a pillar of support for his fellow immigrants, offering his guidance and solace in a place plagued by racial bias. He feels as if he could have accomplished more with his life and been more ambitious, but he didn’t have the means to; he did what he could with what he had. The novel’s opening passage establishes Moses as a role model and mentor to the newly arrived immigrants in London from the Caribbean. “On a cold London evening in the middle of winter, Moses Aloetta takes a bus to Waterloo and waits to meet a man arriving from Trinidad…” (Selvon 23). He’s always doing something for someone, which exposes his soft spot for the immigrant community.

Although he curses his friend for asking him to help Henry, it’s obvious that this isn’t the first time that Moses has gone out of his way to help someone in need. “Because it look to Moses that he hardly have time to settle in the old Brit’n…newspaper and radio rule this country…” (Selvon 24). Moses hardly has time to settle into his own life before he is required to help others, which shows how much people rely on each other in immigrant communities. Unfortunately, Moses doesn’t have anyone to turn to due in part to his unwavering commitment to helping others, which becomes complicated by England’s reluctance to welcome immigrants.

Moses struggles to help his new friends while working to establish his own life and function as part of an ignorant, racist society that masks bigotry under its saccharine-sweet, diplomatic façade. “Now the position have Moses uneasy…they will slam the door in your face and which part they will take in spades.” (Selvon 24-25). Moses is even more worried about how the steady stream of immigrants in London will affect his life, one that he built without any of the guidance he’s providing this next generation. His attitude toward helping his peers is conflicting; he understands that their being here makes things harder for himself in a racist city, but he also feels obligated to aid the “desperate newcomers” (Selvon 26) because it wasn’t too long ago when he found himself in their current position. Moses’s character and journey reflect the inherent tension between embracing the present moment and longing for past familiarity, highlighting the challenges immigrants face in navigating conflicting identities and societal expectations.

We cannot analyze Moses’s character without deeply examining his complex relationship with memory and nostalgia, which play key roles in shaping his identity as his story unfolds. Moses, while hesitant to indulge in nostalgic thought, always feels better when he’s reminiscing on memories of Trinidad with his friends. Moses experiences inner turmoil throughout the novel; he’s constantly kept in limbo by the feeling that he’ll never make enough money to move upward in society, and although this idea sways him to return to Trinidad, he can’t quite bring himself to leave London, a city he has come to love because the immigrants he guides keep his connection and identity to his home alive. “When the sweetness of summer get in him he say he would never leave the old Brit’n as long as he live and Moses sigh a long sigh like a man who live life and see nothing at all in it, and who frighten as the years go by wondering what it is all about.” (Selvon 109-110). Here, Moses is envious of Galahad’s optimism, only capable of the youthful about life in London, an optimism he wishes he still felt.

The impacts of these emotions are epitomized in a moment where Moses introspectively reflects on his life’s profound realizations and the overwhelming sense of aimlessness and restlessness he perceives in the world around him. “Sometimes he think he see some sort of profound realization in his life, as if all that happen to him was experience that make him a better man... As if a forlorn shadow of doom fall on all the spades in the country... As if the boys laughing, but they only laughing because they fraid to cry, they only laughing because to think so much about everything would be a big calamity—like how he here now, the thoughts so heavy like he unable to move his body” (Selvon 141). Moses’s inner struggle is exalted by an overwhelming feeling of nostalgia, his discomfort, manifesting physically and evident in his longing to return to the tropics. Despite his attempts to harden himself for the sake of his loved ones, he remains vulnerable in the toughest of times.

Moses’ experience at the Waterloo Station captures his struggle with nostalgia and memory. “For the old Waterloo is a place of arrival and departure, is a place where you see people crying goodbye and kissing welcome, and he hardly have time to sit down on a bench before this feeling of nostalgia hit him and he was surprise. It have some fellars who in Brit’n long, and yet they can’t get away from the habit of going Waterloo whenever a boat-train coming in with passengers from the West Indies. They like to see the familiar faces, they like to watch their countrymen coming off the train, and sometimes they might spot somebody they know[…].” (Selvon 24-25). The station’s description as a place of both “arrival and departure”, of coming and going, symbolizes the constant flux and transience of life in an urban setting. As Moses observes the emotional farewells and joyous reunions while awaiting Galahad’s arrival, he becomes unexpectedly overwhelmed.

Even though he’s lived in England for the past decade, Moses routinely finds himself unable to resist the appeal of yearning for the West Indies. Nevertheless, he resists pampering in such sentimentality, unlike his friends who, despite being in London for years, still frequent the station in hopes of encountering familiar faces from the West Indies. The narrator criticizes this behavior as “slackness,” implying that they are lazy and irresponsible. However, Moses, despite his aversion to recollection, finds himself unable to suppress his desire to return home.

While The Lonely Londoners portrays Moses as a character who struggles to reconcile with memory and nostalgia among immigrants in 1950s London, it also celebrates the positive, transformative role community can have in the process of making one’s way in the world. The vitality and cohesiveness of this immigrant community are exemplified every Sunday when Moses hosts a congregation of friends in his apartment. They spend this time helping each other find new jobs or places to live and supporting each other in living with the emotional burdens that come along with assimilating to life in a foreign country.

Selvon illustrates moving scenes of such close-knit immigrant communities, revealing them as vital spaces of support and resilience where shared experiences and memories work together in combating the alienation of urban life. On some Sundays, Moses barely even talks, letting the sound of his friends’ words and voices wash over his heart, as he leans back on his bed and dutifully listens to their stories and problems. “Sometimes, listening to them, Moses look in each face, and he feel a great compassion for every one of them, as if he live each of their lives, one by one, and all the strain and stress come to rest on his own shoulders.” (Selvon 139). When they leave, their voices continue in his head, “ringing in his ear, and sometimes tears come to his eyes and he don’t know why really, if is home-sickness or if is just that life in general beginning to get too hard.” (Selvon 140). The fact that Moses feels as if he has lived each of his friends’ lives emphasizes just how close this community of immigrants has become.

Despite their considerable differences, these men understand what their friends are going through because they are going through something quite similar. Moses is a leader, and he feels that his friends’ burdens are his responsibility because he has been in London the longest, therefore taking it upon himself to guide people like Galahad through the trials and tribulations of a monumental adjustment.

In The Lonely Londoners, Selvon masterfully explores the immigrant experience through the lens of Moses, highlighting the profound impact of nostalgia and memory through the character of Moses, and how his cultivation of a close-knit community was what truly saved him. While following along on Moses’s journey, we are invited to empathize with the struggles of immigrant life in this era and to recognize the enduring resilience that can be fostered by a strong sense of loyalty and camaraderie. As we navigate the complexities surrounding race and immigration today, Selvon’s narrative serves as a timeless impactful reminder of the power a community can hold in overcoming adversity and preserving one’s cultural identity in a foreign place.

Works Cited

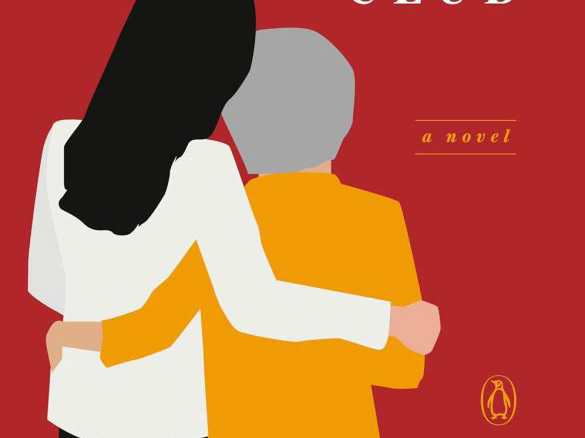

Selvon, Sam. The Lonely Londoners. Penguin Books, 2006.