Far from Paradise: Tourism’s “Single Story” & Jamaica Kincaid’s Narrative Resistance in A Small Place

In her unique, evocative memoir A Small Place, Jamaica Kincaid invites readers into two contrasting realities of her homeland, Antigua—the picturesque tropical paradise marketed to tourists, and the complex, troubled nation experienced by locals. This deliberate simplification of Antigua is exactly what Nigerian author Chimamanda Adichie warns against in her acclaimed TED Talk “The Danger of a Single Story” – the flattening of places and peoples with intricate histories into convenient, consumable stereotypes. Kincaid juxtaposes both tourist and native perspectives in Sections 1 and 2 of A Small Place to reveal how tourism perpetuates a harmful “single story” of Antigua – a story that reduces the island to an exotic paradise, obscuring its elaborate colonial history and modern challenges as an independent nation.

The detrimental effects of the single story show an active preservation of colonial power structures through the commodification of Antigua’s beauty, while systematically erasing its historical counter-narrative of exploitation, resistance, and ongoing neocolonial struggles that continue to shape the island’s present reality. This essay will explore how A Small Place serves as both a powerful indictment of tourism’s role in perpetuating destructive single-story narratives and a reclamation of Antigua’s multifaceted historical truth.

When tourists arrive in Antigua, they come with expectations that bear little to no resemblance to the lived reality of the island with them. Kincaid begins Section 1 with how the tourist exploits Antigua primarily for its weather and scenery. In comparison to the damp and dreary weather of England or North America, the island where “the sun always shines and where the climate is deliciously hot and dry” (4) seems like a paradise. However, Kincaid argues that tourists only superficially interact with this landscape “for the four to ten days [they] are going to be staying there” (4), which prevents them from seeing how such conditions cause the long-term issues of drought and famine for the locals who always live there. Tourists are narrowminded, only able to focus on their interactions with the island, making the lived experiences of Antiguans invisible to them.

* * *

Kincaid focuses on the pitfalls of tourism in Section 1. Tourists in Antigua are usually white, either from North America “or, worse, Europe” (4). She describes the “ugly” sort of satisfaction these tourists take in seeing the comparative poverty and “backwardness” of ex-colonial nations. She explains that the twisted pleasure they take in this comes from a secret relief that “their ancestors were not clever in the way yours were” (17), a relief that the tourist is from the nation of conquerors and not from the nation of the conquered. She notes that tourists sometimes feel that their vacations contribute to the continued single story of places like Antigua, but they won’t let these feelings linger or “develop into full-fledged unease” (10) because all they care about is having fun. Kincaid shows that tourism, as an economic industry Antigua depends on, continues to dominate island life by catering to white visitors.

The international tourism industry systematically erases local history in favor of easily consumable experiences tailor-made for visitors from other places. Kincaid notes that Antigua primarily depends on tourism to succeed economically, meaning that most of the government’s spending goes into the development of this industry instead of bettering the lives of local Antiguans. The government would rather spend money on commercial development for tourists than on restoring educational institutions like the library because tourists are certain to buy “all those awful things that tourists always buy” (48). Given that the government is primarily interested in making money for itself, these projects help it more than developing educational infrastructure would.

The result of Antigua’s simplified narrative is dangerous misconceptions that prevent any meaningful cultural exchange and understanding from happening. Tourists don’t see Antigua as it is because deep down, they refuse to grapple with the uncomfortable aspects of Antiguan reality. Instead of being curious and even concerned about the poverty they see in Antigua, Kincaid believes that tourists are so focused on themselves and their pleasure that sights like the damaged library “would not really stir up these thoughts” (7) of questioning. Kincaid even argues that tourists don’t even see Antiguans at all; they see only themselves and “people like [them]” (13), (white people), enjoying what the island has to offer.

A tourist who does interact with the local people becomes “an ugly, empty thing, a stupid thing, a piece of rubbish” (17) —a phrase Kincaid repeats throughout the text. The tourist takes a voyeuristic role, as a mere observer, a bystander, apathetically witnessing the destitute lives of Antiguans. For example, as tourists have the power and ability to leave the conditions that Antiguans are stuck in, Kincaid says they can even take pleasure in “visiting heaps of death and ruin” because it makes them “[feel] alive and inspired” (16). She believes that even though tourists can be nice people in their own countries, it is once they decide to seek enjoyment in the ruined lives of others across the globe, that they become cruel.

In Section 1, Kincaid alternates between first and second-person perspectives to implicate the reader directly in the power dynamics she critiques. She employs the first person to talk about her own experiences and the common experiences of her fellow Antiguans, using the first-person plural (“we”). She uses the second person (“you”) to describe a kind of person—the tourist—and to implicate the reader as actually being this kind of person or as having the potential to become this person when they travel. Kincaid places the reader in the position of someone she hates and creates feelings of discomfort and responsibility for them. As the tourist is usually ignorant, the use of “you” forces the reader to acknowledge the realities that a regular tourist wouldn’t.

The scathing irony and sarcasm throughout Section 1 expose the absurdity of tourist expectations and simultaneously challenge the reader’s comfortable assumptions. Kincaid uses parallelism to emphasize her arguments through the repetition of “you see yourself” (13) and “you must not wonder” (13-14), which highlights her theory that tourists are self-centered and uninquisitive. Repetition of phrases like this, with slight changes, creates memorable and impactful passages. Her tone throughout this section is accusative, angry, and sometimes sarcastic toward the feelings of tourists. Her anger underscores most of the text and is what drives her passion and vocation to write about the condition of natives’ lives in Antigua.

Chimamanda Adichie’s concept of nkali – the power to not only tell someone else’s story but to determine it as the narrative that holistically defines them, perfectly illuminates the tourist’s relationship to Antigua. Adichie explains power as “the ability not just to tell a story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person.” (09:36). Tourists are often completely unaware of how privileged they are to be able to travel the world freely, or of the power and control it gives them to manipulate the narrative of a place like Antigua for their enjoyment. Economic and political power dynamics between the colonizer and the colonized shape how stories are presented and understood, but an uneven balance leads to the perpetuation and marginalization of an entire people. Keeping the context of nkali in mind, Adichie warns her audience that “[if you] start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, you [would] have an entirely different story” (10:11), reiterating that anytime we tell a story that does not align with the truth of reality and not an imposed truth, it becomes an act of history erasure.

The specialized vocabulary of tourism, comprised of buzzwords like “paradise”, “getaway”, and “exotic”, represents a coded language that reinforces the power imbalance between visitors and locals of Antigua because tourism’s underlying motives descend directly from colonial narratives that positioned the Caribbean as existing purely for European consumption and pleasure. When tourists use words like those above to describe their experiences in Antigua, they are profoundly limiting their cultural understanding by reducing a multifaceted society like Antigua to consumable experiences.

The tourist’s privilege to create and sustain these simplistic narratives about Antigua reflects the larger global power inequalities that Kincaid systematically exposes throughout Section 1. She writes of this imbalance, “They are too poor. They are too poor to go anywhere. They are too poor to escape the reality of their lives; and they are too poor to live properly in the place where they live, which is the very place you, the tourist, want to go” (18-19). Tourism is ugly, Kincaid continues because the locals the tourists stare at cannot escape the harsh conditions of their daily lives in Antigua. The repetition of “they are too poor” is Kincaid using language to emphasize the conditions of the island actively trapping the nation into catering to a global industry.

* * *

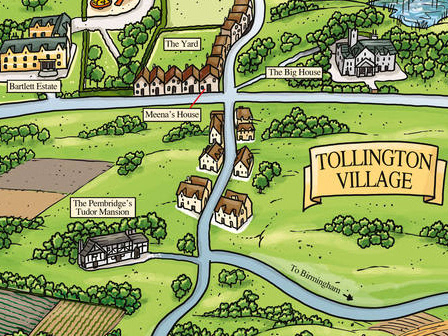

Kincaid dramatically shifts perspective in Section 2, replacing the imagined tourist with her own deeply personal and historical viewpoint as an Antiguan. For her, modern Antigua is much different from the Antigua of her childhood because the English are no longer in power. Antigua’s infrastructure, however, still holds reminders of this time. Kincaid remembers the street she grew up on being named after an “English maritime criminal, Horatio Nelson” (24) and how the center of colonial business and power, fittingly known as High Street, houses colonial-era buildings like the library, post office, the government house, and court.

By sharing her personal experience, Kincaid offers a form of narrative resistance that challenges the tourist’s superficial understanding of the island and showcases the impact of the forced assimilation into English culture on her and her people. She believes that “actual death might have been better” (24) than living under colonial oppressors who pretended to have their best interest. The contradiction of colonial rule Kincaid points out a contradiction of colonial rule: exposing that the English wanted to escape England, but they also wanted to make everywhere just like England—but while the English wanted everyone to become English, they never truly saw the people they colonized as being English. Her deep analysis of the lingering colonial legacy in Antigua reveals how their present struggles directly result from centuries of exploitation.

Kincaid builds multiple narrative layers that distinguish between the superficial “Truth” marketed to tourists and the deeper truths of Antiguan reality. She explains that even thinking about the destruction by the British turns her completely “bitter” and “dyspeptic” (32). She doesn’t understand how people can know what the English did and yet still “tell [her] how much they love England, how beautiful England is, with its traditions” (31). She emphasizes the unfairness of this perspective, as those same English, with their history of traditions, actively oppressed and erased the historic traditions of African peoples, like those taken to Antigua.

Kincaid’s insistence on complexity directly parallels Adichie’s argument that single stories deprive people of dignity by emphasizing difference rather than connection. Adichie furthers her argument when she recalls her American roommate being surprised that they looked different. She reflects on the situation by saying, “In this single story, there was no possibility of Africans being similar to her in any way, no possibility of feelings more complex than pity, no possibility of a connection as human equals” (4:48). In their respective works, both women are advocating for not only an uncovering of the truth that has been systemically erased due to colonialism but for the “Truth” marketed to tourists on travel brochures; descriptions that purposefully exclude any substantial information about the people who suffered while cultivating the land of places like Antigua so that it is simply what tourists expect and want to see.

Memory functions as both a storytelling and political device in A Small Place by preserving histories that tourism narratives actively seek to erase. Kincaid remembers the Czech dentist, who claimed to be a children’s doctor without any credentials. Before seeing them, this doctor made his wife closely inspect the Black Antiguan kids to “make sure that we didn’t smell, that we didn’t have dirt under our fingernails, and that nothing else about us—apart from the color of our skin—would offend the doctor” (28). Kincaid even recalls her own experience, when her mother “examined [her] carefully to see that [she] had no bad smells or dirt in the crease of my neck” (28) before taking her, who had been sick, to the doctor, out of fear that he’d turn her daughter away.

As a work of literature, A Small Place embodies a unique resistance to simplified narratives through its layered structure, shifting perspectives, and refusal to reach an easy resolution. Thinking about how life in Antigua “revolved almost completely around England” (33) enrages Kincaid. The English destroyed her people’s and family’s lives, eradicated their connection to culture and language, and refused to see them as human beings. The critique of tourism in A Small Place extends beyond Antigua to reveal more nuanced patterns of exploitation embedded in global economic systems, as Kincaid pointedly asks: “Have you ever wondered why it is that all we seem to have learned from you is how to corrupt our societies and how to be tyrants?” (34).

Similarly, Adichie cautions that “the single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story” (12:56). Antigua’s institutions are flawed because they are ruins of English institutions that are all in favor of white people. Kincaid refuses to forgive England for their responsibility for Antigua’s destruction and believes that the only (impossible) solution to the problem would be if the British Empire never existed.

* * *

By comparing tourist fantasies in Section 1 with historical realities in Section 2, Kincaid gives us context for examining global tourism’s role in furthering toxic power dynamics. The first sentence that begins Section 2, “The Antigua that I knew, the Antigua in which I grew up, is not the Antigua you, a tourist, would see now. That Antigua no longer exists partly for the usual reason, the passing of time, and partly because the bad-minded people who used to rule over it, the English, no longer do so” (23), combines what both sections aim to convey to readers; Section 1 seeks to place the reader in the position of the tourist to heighten the sensitivity shown for them and to possibly examine their role in being tourists of different places, while Section 2 facilitates such reflection even further when Kincaid becomes vulnerable about her own experiences as a child growing up in colonized Antigua.

In the final section of A Small Place, Kincaid declares that Antiguans don’t actively question “why they are the way they are, why they do the things they do, why they live the way they live and in the place they live” (56). A main consequence of this lack of inquisitiveness is the lack of questioning concerning the corrupt government, leading her to see Antiguans as becoming complacent in efforts to rebel against its continuance. This perspective also prevents Antiguans from looking beyond their small island and seeing their place in global systems of influence. Kincaid thinks Antiguans have thoroughly absorbed “the degradation and humiliation of their daily lives” (69) to the point that they speak about their hardships as if they were “tourist attraction[s]” (69) they can see only from a distance.

Institutions like the Mill Reef Club and the Hotel Training School prove to Kincaid that Black Antiguans are still servants for visiting white people, but that many of them are blind to the connections between past and modern structures of servitude. The celebration of the Hotel Training School, which “teaches Antiguans how to be good servants, how to be a good nobody” (55), and of the first Black people to dine in the Mill Reef Club shows Kincaid that Antiguans have been made complicit in their continued exploitation.

Kincaid’s criticism provides food for thought when understanding contemporary global tourism patterns and their relationship to neocolonial economic structures. Neocolonialism refers to when a colonizer will continue to colonize a place even after granting them their freedom, and although Antigua gained independence in 1981, 7 years before A Small Place was published, the island’s economy has yet to escape its heavy reliance on tourism and the single story of it simply being a tropical paradise; the very factors that have bound them in metaphorical (and literal) chains for many years. In other words, it’s a constant cycle of marginalized people having their identities become putty in the hands of selfish colonizers.

A Small Place challenges us to imagine a future of tourism representation that acknowledges both historical complexity and power imbalance. In Section 4, despite describing Antigua’s natural beauty poetically and respectfully, Kincaid later states that the island’s geographical features are all like “a prison, and as if everybody inside it were locked in” (79). Kincaid explains that Antiguans can’t see how little their lives have changed because their landscape is so unchanging, and this constancy influences their static understanding of themselves. She sees that despite gaining emancipation, Antiguans were freed only “in a kind of way” (80). Black Antiguans continue to be ruled by crooked powers and oppressed on their lands by foreign economic systems. Thus, while surrounded by an unreal, unchanging landscape, the people of Antigua find it hard to break from their confinement and truly be free.

* * *

Both Kincaid and Adichie demonstrate how single stories function as instruments of power that maintain the unequal relationship between the colonizer and the colonized. Adichie explicitly names this power dynamic nkali, which we know is the ability for someone in power to not only tell someone else’s story but to make that story define them. When Kincaid writes, “That the native does not like the tourist is not hard to explain... the tourist is someone who has the ability to leave [their] own banality and boredom” (18-19), she directly exposes this same power imbalance.

In A Small Place, Kincaid transcends the simple binary of narrative versus counter-narrative by showing us how all stories exist within tangled webs of power, history, and resistance, declaring that “An ugly thing, that is what you are when you become a tourist, an ugly, empty thing, a stupid thing, a piece of rubbish...” (17). Ultimately, both Kincaid’s A Small Place and Adichie’s “The Dangers of a Single Story” serve as a call to action that demands our recognition of multifaceted truths of places like Antigua, even when those truths make us uncomfortable as outsiders.

To conclude, I’ve found no manner more suitable to do so than to quote Adichie’s final remarks during her TED Talk: “When we reject the single story, when we realize that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise” (18:16).

* * *

Works Cited

Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. “The Dangers of a Single Story”. Ted: Ideas Worth Spreading, July 2009, https://youtu.be/D9Ihs241zeg?si=DQ9wiM7aKDrMG8eW

Kincaid, Jamaica. A Small Place. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Groux, 1988.